Vishnu Makhijani

Soumitra Chatterjee, the doyen of Bengali cinema who passed away on November 15, 2020 aged 85, leaving behind an oeuvre of over 250 films – a staggering 14 of them directed by Satyajit Ray – five books, four poetry collections, three dramas and an array of paintings, had once remarked that he would have become a carpenter had he not become an actor.

It might sound flippant but his admiration for the craft of carpentry was genuine, revealing that he believed in creativity that was useful, something that would be helpful to people, says the first biography of the actor in English set to release on his 86th birth anniversary on January 19.

“Soumitra Chatterjee’s legacy goes well beyond his body of work in cinema, which on its own will probably never be matched. He is best known for being the favoured actor of one of the world’s greatest directors and remains one of the most visible representatives of Indian cinema abroad,” Arjun Sengupta, co-author of “Soumitra Chatterjee – A Life in Cinema, Theatre, Poetry & Painting”, (Niyogi Books), told IANS in an interview.

“However, the range of his accomplishments emerges from his unique nature. He understood the value of education and culture and all through his life remained unwavering in his belief on the importance of social responsibility and artistic integrity. He disdained stardom if it got in the way of his beliefs as an artist.

“He had a varied career that went beyond films. His belief in art and the responsibility of an artist ensured that he brought the same seriousness and breadth of learning to no matter what he did. He was a resolute champion of Bengali language and culture, choosing to dedicate himself to Bengal rather than look for a more national popularity through Hindi cinema. For these reasons and more, he was one of Bengal’s greatest ambassadors to the world,” Sengupta added, who teaches English Literature at the St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata, with previous stints at Scottish Church College and Presidency College.

A considerable amount of research went into the book, during the writing of which Chatterjee was personally involved.

“The research involved going through a number of books that have been written on him and about Bengali cinema in general. This allowed me to place his achievements in a greater socio-historical context. Mr Chatterjee was kind enough to lend us his ‘Gadya Samagra’, a collection of his writings for reference. His writings gave me important insights into the kind of person he was. It also allowed me to gain a deeper understanding of his pursuits as a thespian, painter and poet.

“I also watched and re-watched several of his films, studying the smallest details to appreciate his craft better. All this was supplemented by hours of interviews of Mr Chatterjee,” Sengupta said of the effort he and co-author Partha Mukherjee, a Kolkata-based Freelance Writer-cum-Documentary Filmmaker put in.

To this end, what the book reveals is that Chatterjee did not believe in looking back, and even at 85, kept looking forward to new challenges. This is probably why his death is not a coda because he had so much more to contribute to the world of theatre, art and cinema. Thus, the book is a celebration of his multi-faceted creative genius and his role in representing Bengal on the world stage.

The book explores the making of Chatterjee through his early years and his relationships with theatre exponent Sisir Bhaduri and Satyajit Ray. His 14 films with Ray are a testament to his versatility and virtuosity. As an actor he refused to settle in a comfortable groove and constantly looked out for fresh challenges. Throughout his theatrical career, he not only adapted and directed several acclaimed plays but kept returning to the stage for sustenance and inspiration. His poetry and art are more personal and offer an insight into his idealistic and cultured soul.

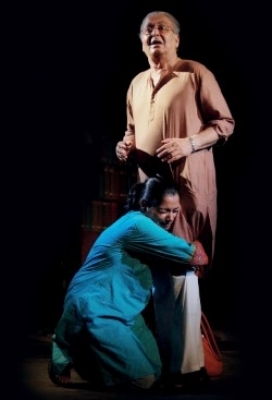

Analysing the most important roles of his career, and charting the single-minded dedication and passion that he brought to each one of them, the book reflects on Chatterjee’s stardom and longevity in an industry that saw great changes during his lifetime. Featuring 70 unique photographs, the book is a visual treat and illuminates the versatile facets of a towering artist – a Renaissance man – who along with Ray brought Bengal to the cinematic world.

What it also brings out is that Chatterjee’s poetry and paintings are a distillation of an idealistic sensitive soul. He is forever caught between a desire to escape through memory to an idealised past and a need to engage with the troubles of reality. His art is even more private and personal than his poetry. His paintings are oddly beautiful and could be quite eerie, too. They are nevertheless striking and speak of a vivid and bold personality.

Chatterjee refused to work in other languages. He consciously resisted the lure of Bollywood as he felt his performance gained a lot of credibility from his proficiency in the Bengali language and wondered if it would be the same in a language in which he was not fluent.

His loyalty to his Bengali identity determined many of his decisions in his career. It turned out to be a wise choice because with the help of Satyajit Ray and other acclaimed directors, he managed to stay close to his roots while turning out performances of universal relevance. He has worked in Bengali cinema but in his legacy he belongs to world cinema.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be reached at vishnu.makhijani@ians.in)

COMMENTS